Book Review: Build, Baby, Build

In Build, Baby, Build, economist Bryan Caplan tries a new strategy that, as far as I know, no libertarian has ever attempted before: actually communicating to normal people about how a free-market policy could improve their lives.

Alright, I’m kinda joking here, but I’m also kinda serious. Libertarians are extremely bad at this. Take the 2016 election for example. With the US facing two wildly unpopular candidates from the two major parties, many voters were looking for an alternative — the perfect opportunity for libertarians to market themselves! But rather than seizing this rare opportunity, the Libertarian Party focused instead on debating whether drivers licenses should exist and, um…… this.

That’s why Build, Baby, Build is so refreshing. Rather than focusing on some abstract philosophy about how to apply the non-aggression principle, Caplan instead focuses on a real, concrete issue that impacts most people’s lives: the high cost of housing. He presents a straightforward case: housing is expensive because its supply is artificially restricted by excessive government regulations, and the best way to make it cheaper is to remove these regulations and allow more housing to be built.

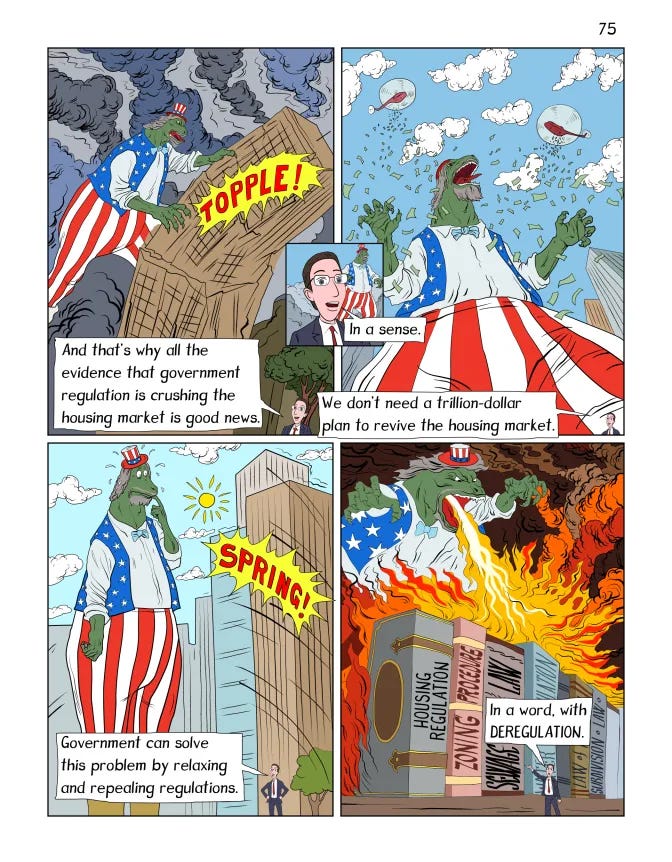

Also, it’s a graphic novel, so the pages look like this:

I’m a big fan of this format (which Caplan has used before). I think it’s great for communicating ideas in a way that’s entertaining and more accessible than a textbook or research paper. For example:

On this page, Caplan rips up a plot of supply and demand curves, and instead explains in intuitive terms why increasing supply leads to lower prices — not because the developers (who are portrayed as greedy fat cats) are just being nice and lowering prices out of the goodness of their hearts, but because they want to make as much money as possible, and this means they have to compete with each other to attract customers by lowering prices.

So yeah, I like the comic book style. Bryan Caplan’s pretty funny and this is a good format for his humor. I also think the illustrations are pretty good, even though they’ve gotten some criticism.

At the same time (and maybe fittingly for an economics book), the use of the comic book format involves a tradeoff between entertainment/accessibility and rigorous literature review. For example, Chapter 3 of the book is called “The Panacea Policy,” and makes the case that a wide variety of problems in society could be solved or improved with housing deregulation — inequality, social mobility, crime, falling birthrates, homelessness, etc. I found this part of the book to be a bit lacking in terms of supporting evidence. Every case Caplan presents here sounds plausible but there isn’t enough evidence presented to reach a solid conclusion.

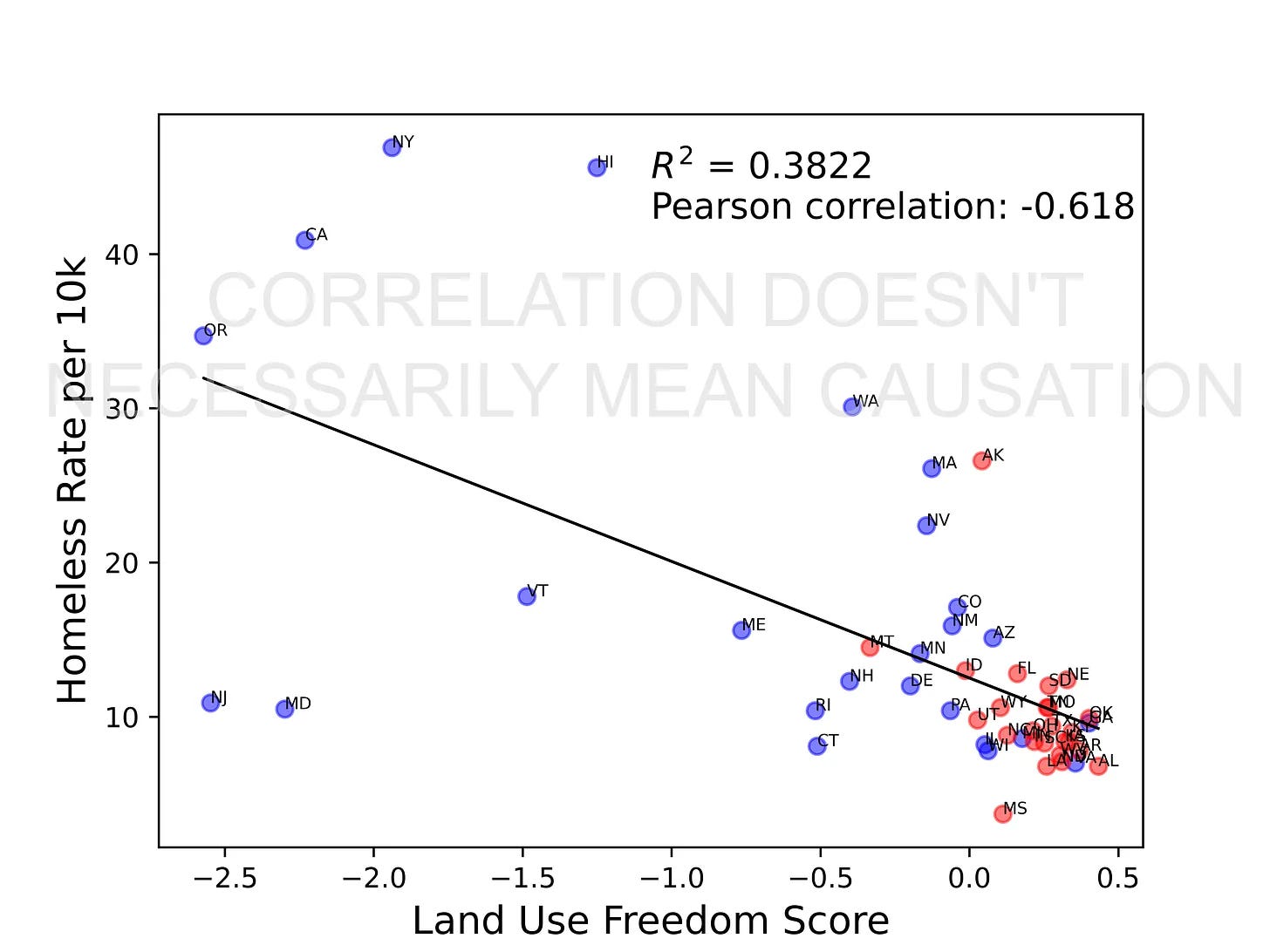

Take homelessness, for example. I’ve written before about the relationship between homelessness and land-use/housing regulations, and there appears to be a correlation between them, at least at the state level.

But there are so many other relevant variables that it’s tough to say if this is a causal relationship or not. For example, it looks like the blue states tend to have more homelessness than the red states, so this is potentially a confounding variable — I probably could have plotted the homelessness rate against a lot of other variables that differ between red and blue states (gun ownership, church attendance, BBQ restaurant quality, etc), and shown a non-causal correlation between them.

Anyway, I think it’s plausible that excessive housing regulation causes homelessness, but to be fully convinced of this (and several other minor claims throughout the book) I’d need to see something like a Scott-Alexander-style deep dive on the literature or formal academic review of all the relevant studies, and that isn’t really compatible with the comic book format1.

So that’s probably my biggest criticism. And again, it isn’t even really a criticism — it’s just an acknowledgement that by using the fun comic book format, Caplan is navigating a tradeoff between entertainment/accessibility and rigorous literature review, and prioritizing the former at the necessary expense of the latter. And that’s probably a good thing that we need more of!

Anyway, I think it’s great book overall. Despite my nitpicking and skepticism around some minor claims, the fundamental argument that we should deregulate housing in order to reduce housing prices is solid and convincing, and presented in a fun and entertaining format. Caplan does a good job of making this case, and responding to all the usual counter-arguments. I definitely recommend the book, and you can buy it here if interested.

Lastly, I’d like to end this review on a note of cautious optimism. At one point, Caplan points out YIMBYism isn’t a strictly partisan issue with one party in favor and the other against. Rather, it’s a common sense solution to high housing costs that either party could pick up and run with. And in other countries, this is actually happening! In the UK, the left-wing Labour Party is promising YIMBY solutions to bring down housing costs… and they’re on track to win the next election and oust the incumbent Conservatives. In Canada it’s the opposite — the Conservatives are promising YIMBY solutions to bring down housing costs… and they’re on track to win the next election and oust the incumbent Liberals! Maybe more American politicians will start to notice that this is a winning issue, and I think Bryan Caplan’s advocacy could help us towards that goal.

For some of the claims Caplan does cite specific studies, but even in these cases I’m still cautious to draw conclusions from a single paper without seeing a broader literature review or meta-analysis. For example, Caplan presents a study (Branas et al. 2018) in which some vacant lots in Philadelphia were randomly selected for landscaping, fencing, and maintenance, and areas around them subsequently had a decrease in crime. I was skeptical of this, did a bit of googling, and found one successful replication (Gong et al. 2022) and no failed replications — so that claim passes, at least for now! But I don’t have enough time to go down a rabbit hole of papers for every claim made in the book, so there are several claims (like the homelessness one) that I consider plausible but not conclusive.